Reviews Anthony Dean Griffey, tenor and Warren Jones, piano The opening set was by John Dowland (1563-1626). The audience responded warmly to these English songs written some 400 years ago. Mr. Griffey’s diction was precise and the text came through clearly: Come Again speaks of the delight of lovemaking and the desire to return to that state of bliss and then of the pain when the affair ends. The phrasing may be old fashioned but the feeling is most contemporary. The text of What if I never speed? reads “Come, come, come while I have a heart to desire thee…for I will either love or admire thee.” With clear-cut rhythms and simple harmonies Fine knacks for ladies is a peddler’s pitch at a country fair and also a metaphor for love. The performance was delightful. Moving forward 200 years we heard two German language songs from Schwangesang (Swan Song) by Franz Schubert (1797-1828), a set of songs published the year after Schubert’s death. The emotional feelings of Liebesbotschaft (Love Message) were carried by Mr. Griffey’s deep well of sound. In Standchen (Serenade) the singer waits at night, begging the beloved to come to him in the grove where the nightingales sing their sweet lament. His voice so sweet, the piano so mellow they could have melted the hardest of hearts. Though the emotional expression gave us the feelings of the songs, song texts in the program booklet would have been helpful and the song listings should have been edited by someone knowledgeable of art song, though the program did offer extensive biographies of the performers. Mr. Jones next gave a verbal introduction for three selections form Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Opus 118. The art of the accompanist is not the same as a concert pianist and the difference was visible in this truly lovely romantic music with no overheated bravado in the two Intermezzi. That was saved for Ballade, a piano form invented by Chopin and used by later composers. By the time he returned to the stage to sing two songs by Ernst Chausson (1855-1897), Mr. Griffey had learned that we did not have song tests and solved the problem by reading us the poems in an English translation before he sang in French Serenade Italienne, Op. 2. It is a wonderful love song that dripped with passion as surely as the boatman’s oar dripped with water. A lover sings under his lady’s window on the canal. The piano stood in for the original guitar. Le temps des lilas (The time of lilacs and roses) warns a naïve young woman that once love has passed it will not come back again. There was no sunshine in this song, only especially impassioned singing. After intermission we heard songs by 20th century American composers. The Samuel Barber (1910-1981) Opus 10 on text by James Joyce serenely suggests falling rain in the piano part of Rain Has Fallen, a melancholy song in which the lover asks the beloved to remember their past happiness. Of the middle song, Sleep Now, Carol Kimball says the song lies a minor third below the first and last songs in C minor, a triptych corresponding to a relationship that begins lyrically in Rain Has Fallen and ends in the stormy dissolution of I Hear an Army. The emotional range of the performance goes from dramatic to a sad lullaby to a ferocious song of froth and foam, closing with “Why have you left me alone?” From here the concert moved into the folk songs set by Aaron Copeland titled Old American Songs. From set one (there are two sets, six songs each) we heard The Boatman’s Dance with a smile in the voice, and my favorite from his set, the homespun humor of The Dodger. Originally a political campaign song from 1890, it was performed with just the right amount of support from the piano and perfect diction form the singer who told us that you can’t trust politicians, preachers nor lovers. The audience was totally engaged. Long Time Ago is a pretty lyrical setting and Mr. Griffey’s low notes were a deep gurgle. In Simple Gifts the diction was a bit too mannered for this Shaker folk hymn. “Mon” instead of “Man” in A Simple Song by Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) is another example of his cultivated pronunciation. My personal preference is for American English in American songs. A favorite song of mine followed, Early in the Morning by Ned Rorem. It is the voice of an exuberant young American at a Paris café on a sunny summer day. Over the Rainbow by Harold Arlen (1905-1986) was a triumph of an operatic tenor giving a familiar tune his all. The encore was This Little Light of Mine in the less well-known arrangement by African-American composer John W. Work, Jr. (1871-1925). It is a very gentle take on the usual text and a signature encore piece for Mr. Griffey. If you’d like to hear more of this mighty, lyric tenor, there is a DVD of Mr. Griffey performing the title role of Britten’s Peter Grimes at the Met. Anthony Dean Griffey Master Class

Mr. Griffey is a Highpoint, NC native and was an unlikely opera singer, being very shy and looking more like a football player than a lyric tenor. He played trumpet in his high school band but did not sing in the chorus. Somehow his choral director discovered his singing voice and insisted that he sing in the school’s annual talent show. Being a very shy person, he strongly resisted. Her persistence caused him to finally agree to sing. When the day of the concert arrived the audience erupted into exuberant applause which changed everything for the young tenor. Realizing his gift he decided to commit himself to singing and enrolled in Wingate University in SC as a vocal performance major. From there he went to the Eastman School of Music, the Juilliard School and finally The Metropolitan Opera’s Lindemann Young Artists Program. While at Juilliard he studied with Beverly Peck Johnson who “changed his life”. I know exactly what he meant because my own teacher at Juilliard, Ellen Faull, was a student of Ms. Johnson and I experienced the same type of life-changing experience after studying with her for only a few weeks. As Mr. Griffey began to work with the singers we got a glimpse of those life-changing technical ideas. The first student was a lovely lyric soprano who sang “Liebesbotschaft”, the first song from the Schubert cycle, Schwanengesang. As with all four singers, Mr. Griffey began by asking her why she loved to sing. Being the first singer she was put on the spot a bit but finally was able to articulate a reasonable answer. This is the type of question that, although essential, most young singers don’t think about very often. The technical, musical and dramatic expectations for today’s singer have never been greater and reminding yourself often about why you’re doing this was good advice from one who knows. Our young soprano’s first rendition of this well-known German art song was very good. She was obviously well prepared and showed considerable potential. Typical of a young singer, her chest voice was not connected to her head voice and her high notes did not match the rest of her sound in volume. Mr. Griffey asked her to sing on the very bright and somewhat spread [æ] vowel (like the sound of the vowel in the word fat). Our soprano seemed a bit uncomfortable with this sound but she did her best. I was not surprised with her response because this is not an Italian vowel, the language we usually think of as “good for singing” and the one with which most of us begin voice study. This sound is the hallmark of the Johnson/Faull technique and can be very effective in giving projection and presence to a voice, especially to American singers who speak and sing farther back in the mouth than would an Italian singer. This sound can work like a charm for a soprano or tenor but conversely, can be ineffective and even tension producing for the darker, richer sounds of the mezzo or baritone. The famous dramatic soprano Birgit Nelson sang daily on this vowel and Marilyn Horne also considered it to be very effective. In my studio I usually reserve this practice sound for later, when I know the singer and the voice well, because this sound is always met with considerable skepticism. My first reaction at my early lessons with Ms. Faull was to consider looking for another voice teacher. However, I stuck it out and within a month or so I was sold on the new technique. My plain vanilla soprano grew into a distinctively colored sound that projected easily into a large hall. I was also able to sing with more control, shaping phrases with ease. Portimenti (a smooth slide from one note to another in which intervening notes are not separately discernible) and messa di voce (a technique that involves a gradual crescendo and decrescendo while sustaining a single pitch) became much easier. I began lessons in the fall and by the following spring I had won three major vocal competitions and my church choir director was telling me to “tone it down." Needless to say I was ecstatic with my new “powerful” sound. Now, back to our young singer. After singing the entire song on [æ] there was a noticeable increase in projection and presence in her sound. In time I think this singer would also be able to bridge the connection to her higher register creating one complete, connected vocal line with stronger high notes. She has the perfect instrument for this technique. Mr. Griffey worked with three other singers who displayed equally effective responses to his instruction. What I liked even better than his technical skills was his sense of responsibility and commitment to the art of singing. His humility and generosity of spirit was such a wonderful example for all of us, teachers and students alike. I am very grateful to Old Dominion University and Dr. Brian Nedvin for bringing this world-renowned singer and teacher to our community. Back to Top

|

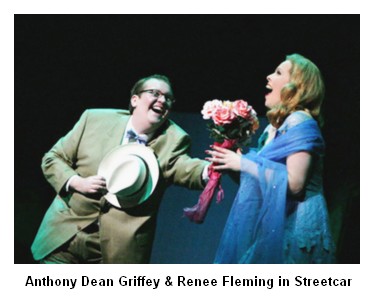

The cover photo of the program booklet brought to mind our first awareness of Anthony Dean Griffey. In the role of Mitch, he is handing a bouquet of flowers to Renée Fleming as Blanche Dubois, in the opera A Street Car Named Desire by André Previn (1989) based on the play by Tennessee Williams. This program did not present any music from Street Car though if you are interested there is a DVD of the complete opera available. But this recital was a perfect introduction to art song for college students who were the majority of the capacity audience at Chandler Hall. It was an inviting entrance into the world of classical song. A world-class lyric tenor, Mr. Griffey sang accessible art song repertory, mostly in English, accompanied by one of the best known art song accompanists in America, Warren Jones.

The cover photo of the program booklet brought to mind our first awareness of Anthony Dean Griffey. In the role of Mitch, he is handing a bouquet of flowers to Renée Fleming as Blanche Dubois, in the opera A Street Car Named Desire by André Previn (1989) based on the play by Tennessee Williams. This program did not present any music from Street Car though if you are interested there is a DVD of the complete opera available. But this recital was a perfect introduction to art song for college students who were the majority of the capacity audience at Chandler Hall. It was an inviting entrance into the world of classical song. A world-class lyric tenor, Mr. Griffey sang accessible art song repertory, mostly in English, accompanied by one of the best known art song accompanists in America, Warren Jones. After an amazing recital the night before displaying a wonderfully rich voice, superb musicianship and dramatic intensity, I was anxious to hear what Anthony Dean Griffey would have to say to our young Old Dominion University voice students. He began by addressing the audience, giving us a bit of his background, sharing some of his philosophy about why he sings and inviting us to participate and comment.

After an amazing recital the night before displaying a wonderfully rich voice, superb musicianship and dramatic intensity, I was anxious to hear what Anthony Dean Griffey would have to say to our young Old Dominion University voice students. He began by addressing the audience, giving us a bit of his background, sharing some of his philosophy about why he sings and inviting us to participate and comment.