| GSA & VCU Side by Side: Mahler 1 |

|

|

ReviewsDumbarton Oaks Chamber Music Concert On a sparkling summer afternoon some fifty listeners, about half of which were six to twenty years old, and eighteen instrumentalists gathered for a chamber concert of music by Bach, Beethoven and Stravinsky. The Hixon Theater was set up with performers and audience on the same level— no stage platform. The feeling was open and the musical experience was intimate. You also need to know that the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra Process ™ was used. It is a method that places democracy at the center of rehearsal and performance. There is no conductor; rather leadership of the ensemble is shared around, changing from piece to piece. Leadership roles shift from performer to performer for each work presented. The performers were teachers and present and former students of the Governor’s School for the Arts Instrumental Music Department. As the program began, not twenty feet from where we sat Noemie Chemali appeared and played the Gavotte en Rondeau from J.S. Bach’s Partita No. 3 in E. major, BWV 1006. In typical dress for all the performers, black casual blouse, slacks and flat shoes, she played with accuracy and was especially pleasing in the two voice duet section. After she finished, she smiled and exited the door right. My description of what we heard is greatly informed by Paul Griffith’s book, Stravinsky. The first piece, Dance, opens with the earthy sound of Rite of Spring, though the material is more simple and the fragments and reversals recall a peasant fiddler. Tiny motifs break-up the symmetry of any proposed melody. Eccentric, the second piece, has repeated swoops of strings, a sort of fragment of a sour tune interrupted by plucked strings. The rhythmic dance that grows out of this suggests a clown that jumps from one bizarre posture to another. The third piece, Canticle, opens as a sad melody, harmonic but with small displacements. Stravinsky carried these pieces with him during World War I, revising and later orchestrating them. There is humor here of a sophisticated mind relating to the simplicity and ignorance of peasant songs and dances. The program concluded with a major work by Stravinsky, Concerto in E-flat for Chamber Orchestra. Known as “Dumbarton Oaks” it was commissioned (1937-38) by Mr. & Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss for performance at their home, Dumbarton Oaks, in Washington, D.C. on May 8, 1938, conducted by Nadia Boulanger. The third, Con moto, movement is as if a great machine is rolling, creating a slow, staccato pulse in the cellos, punctuated by woodwinds. Though with a lighter touch later, the bassoon and still later the horns (Matt Gray and Becky Peppard) are prominent. The cellos return (Dionne Wright Smith and Jeff Phelps) with plucked and bowed strings building momentum and propelling the finale to an abrupt end.

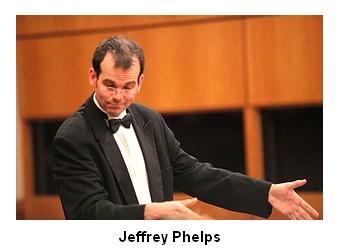

In a continued series of symphonic collaborations titled “Side by Side," Virginia Commonwealth University Orchestra, Daniel Myssyk, conductor, joined the Governor’s School for the Arts Orchestra, Jeffrey Phelps, conductor, for a stunning performance of Gustav Mahler’s (1860-1911) Symphony No. 1. Though the symphony has been characterized as a wonderful sound picture of nature reawakening in spring, in my mind’s eye at least, in the beginning it is dawn breaking. As first light appears in the east, birds are singing. Things begin as hushed, sustained seven-octave harmonics in A, played with an eerie calm, especially by the dusky strings with the oboe occasionally commenting. Silent moments between bird calls, mostly by flutes and hunting horns in the distance slowly emerged in comprehensible themes played with increasing energy. Now that the universe is in tune the singing flow begins. Raucous joy is breaking out. This exuberance gives way to lyrical passages with overlapping bird calls. There is a pensive feeling as we seem to build toward a climax. Instead, the music returns to the restrained orchestral colors of nature. The first movement ends with percussion in full glory with all strings playing. Conductor Myssyk ignored the applause after the first movement. When it stopped he began the second movement with all-encompassing, full orchestral sound. After the headlong rush Mahler settles into a lyrical, easy flow. Cellos and woodwinds are dominant. A lyrical dance builds into a great structure that seems to reach to the heavens until it suddenly crumbles.  The third movement begins with the nursery rhyme Frère Jacques played as a death march by a muted double bass and oboe. Suddenly it breaks into a fast, raucous gigue in the style of a Klezmer band, which his first audience found unsettling. Today we know this music as the refrain from If I Were a Rich Man from Fiddler on the Roof. What Mahler is describing from boyhood memory is a child’s coffin [his brother] leaving the house to a blast of merriment from the tavern. (Norman Lebrecht, Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed Our World. In the fourth movement the lilting tune of cello and oboes is melodious cowbells from hillsides with lush meadows bathed in sunlight and creates a sense of great contentment. And yet there are deep ominous undertones. A storm is building, the birds sing more cautiously. An oom-pa-pa band marches through and the mood shifts, momentarily unsettling, until it quietly dies away. Drums and cymbals burst the silence—the storm has begun with thunder, lightning strikes and drenching rain. All those horns take over. The energy is restrained, winding up tighter and tighter. It seems so right that the energy of young students is meeting the energy of a young composer in such a brisk, incisive performance. Back to Top Printer Friendly Format Back to Review Index Home Calendar Announcements Issues Reviews Articles Contact Us |

Before I talk about the performance, we should know that Dionne Wright (now Dionne Smith), a local cellist of note, received one of twenty grants nationwide to immerse herself in her creative work of teaching and playing. The grant from the National Artist Teacher Fellowship (NATF) through the SURDNA Foundation made the concert possible.

Before I talk about the performance, we should know that Dionne Wright (now Dionne Smith), a local cellist of note, received one of twenty grants nationwide to immerse herself in her creative work of teaching and playing. The grant from the National Artist Teacher Fellowship (NATF) through the SURDNA Foundation made the concert possible. In Ludwig Van Beethoven’s Three Duos for Clarinet and Bassoon, WoO 27: No 1, Dionne Wright Smith on cello performed with John Winsor on clarinet. We had our first conversation with her a few years ago after a performance with the Hardwick Chamber Ensemble of which Mr. Winsor is composer in residence as well as clarinetist. They played with enthusiasm and professional polish. The happy-go-lucky first movement gave way to a soulful clarinet in the second where the statements were delicately stitched together by the cello. A delightful dance brought the piece to a satisfying conclusion. Surprised that Beethoven composed such a happy piece, we learned from the Grove Dictionary of Music that attributing WoO 27 to Beethoven is of doubtful authenticity .

In Ludwig Van Beethoven’s Three Duos for Clarinet and Bassoon, WoO 27: No 1, Dionne Wright Smith on cello performed with John Winsor on clarinet. We had our first conversation with her a few years ago after a performance with the Hardwick Chamber Ensemble of which Mr. Winsor is composer in residence as well as clarinetist. They played with enthusiasm and professional polish. The happy-go-lucky first movement gave way to a soulful clarinet in the second where the statements were delicately stitched together by the cello. A delightful dance brought the piece to a satisfying conclusion. Surprised that Beethoven composed such a happy piece, we learned from the Grove Dictionary of Music that attributing WoO 27 to Beethoven is of doubtful authenticity . Jeffrey Phelps of GSA and three Instrumental Music Department students, Ms. Chemali and Ryan Tolentino, violins and Andre Magalhaes, viola, joined in Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914 rev. 1918) by Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971).

Jeffrey Phelps of GSA and three Instrumental Music Department students, Ms. Chemali and Ryan Tolentino, violins and Andre Magalhaes, viola, joined in Three Pieces for String Quartet (1914 rev. 1918) by Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971). Stravinsky was in a Swiss sanitorium suffering from tuberculosis, as was his wife and two daughters. He recovered but his wife and one daughter succumbed. There he studied the music of Bach and seems to have been influenced by the Brandenburg Concertos. Though there are no fugues in his Concerto in E flat, there are passages in a fugal style. The opening movement, Tempo giusto, begins with string outbursts that frame and support woodwind excursions. There is a wide-open American sound we usually associate with Copland. The plucked basses (Chris Brydge, Elizabeth Barth) are used as percussion. In the more spare Allegretto movement, the flute (Patti Watters), clarinet (Jonathan Carr) and bassoon (Jim Nesbit) lead by turn in dialogues with grouped strings, both rhythmically and melodically. The violinists were Allegra Havens, Tracy McDonald and Ryan Tolentino; the violists were Norbrian Ronase, Madeleine Hofelich and Caleb Paxton.

Stravinsky was in a Swiss sanitorium suffering from tuberculosis, as was his wife and two daughters. He recovered but his wife and one daughter succumbed. There he studied the music of Bach and seems to have been influenced by the Brandenburg Concertos. Though there are no fugues in his Concerto in E flat, there are passages in a fugal style. The opening movement, Tempo giusto, begins with string outbursts that frame and support woodwind excursions. There is a wide-open American sound we usually associate with Copland. The plucked basses (Chris Brydge, Elizabeth Barth) are used as percussion. In the more spare Allegretto movement, the flute (Patti Watters), clarinet (Jonathan Carr) and bassoon (Jim Nesbit) lead by turn in dialogues with grouped strings, both rhythmically and melodically. The violinists were Allegra Havens, Tracy McDonald and Ryan Tolentino; the violists were Norbrian Ronase, Madeleine Hofelich and Caleb Paxton.  A twenty-nine year old Mahler conducted the first performance of his first symphony on November 20, 1889, one-hundred twenty-four years ago. At the time he was conductor of the Budapest Opera in Hungary and called his work a Symphonic Poem in two parts. The version we heard was much revised from the one he conducted there. His Budapest audience liked the first part. But the beginning of part 2, which we know as the third movement, upset their sensibilities. But more of that later.

A twenty-nine year old Mahler conducted the first performance of his first symphony on November 20, 1889, one-hundred twenty-four years ago. At the time he was conductor of the Budapest Opera in Hungary and called his work a Symphonic Poem in two parts. The version we heard was much revised from the one he conducted there. His Budapest audience liked the first part. But the beginning of part 2, which we know as the third movement, upset their sensibilities. But more of that later.