| St. Petersburg String Quartet Wren Masters |

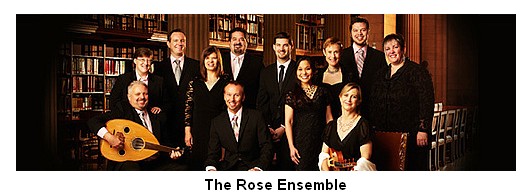

ReviewsThe Rose Ensemble One of the most interesting, unusual and ravishing concerts of the year took place April 23rd at Virginia Wesleyan’s Hofheimer Theater, when the Rose Ensemble presented “Land of Three Faiths: Voices of Ancient Mediterranean Jews, Christians, and Muslims.” The renowned early music ensemble explored religious and secular music of Christian plainchant, the Sephardic Jewish tradition, and traditional Arabic and Bedouin songs. It was magic—pure, passionate and utterly thrilling.

Their meticulous research provided the audience with excellent programs that included not only the texts and translations of the songs but a fascinating look at the history and cultures from which the unfamiliar music arose.  Pues que tú, Reyna del çielo was a villancico by Juan del Encina, from the time of Queen Isabella. It extolled Mary as Queen of Heaven. The women began, accompanied by percussionist Tim O’Keefe’s hand drum, then added the men’s voices.

The Rose Ensemble’s founder, tenor Jordan Sramek and soprano Kim Sueoka began Porque llorax blanca niña? (“Why do you cry, fair maiden”), a blend of two Sephardic stories. Snaidas, Chalmers and Kachelmeier were added to the mix, with Sramek’s delicate psaltery, ’ud, vielle and medieval tambourine. In the humorous but no less exquisite Coplas de las flores, each flower bragged about its ability to praise God. Repetitive harp arpeggios and variations accompanied the plainchant Cives caelestis patriae, from the Book of Revelation, in which the devastatingly beautiful voices of Sueoka and Snaidas soared with breathtaking micro-ornamentation. An anonymous 14th-century English instrumental featured Ginna Watson’s harp. Sueoka’s voice floated gracefully in “Hanna has seven sons,” a Sephardic Hanukkah song. Ten Brink intoned a traditional Sephardic psalm from Istanbul, joined by Sramek and Chalmers. Their unison in the micro-ornamentation was mind-boggling. Another liturgical song pleaded insistently for God to “answer us, answer us.” How could God resist such music? Dotted triple rhythms brightened a Mardi Gras song; then two cheerful Sephardic songs recounted Hanukkah recipes. (What’s a celebration without feasting?) The 13th-century Spanish Cantiga #424 was a ravishing song about the Three Kings who came to Bethlehem with gifts. A Hispano-Arabic muwashaha—traditional Arabic poetry set to music— had Sueoka’s pure tone and precisely controlled vibrato. David Burk closed his eyes and grooved in the Turkish instrumental, cranking his ’ud into faster and faster rhythms. I hadn’t seen anything like this since the Silk Road folks were in town. Tim O’Keefe’s drum riffs and counter-rhythms, especially a long 9/8 section, oddly subdivided, were simply amazing. Harp, frame drum (with a rainstick sound) and ’ud accompanied Morena me llaman, sung high and clear by Snaidas, who acted out its story with wit and sly humor. The program notes state that the music and poetry of two traditional Bedouin songs probably contain the most archaic surviving features of Near Eastern folk music. In a dramatic paraliturgical poem, Et Sha’are Ratzón, the cantor’s voice imitates the sound of the shofar. It’s difficult to describe, but riveting to hear. For the final selection, a Balkan Sephardic song about Abraham’s being saved from king Nimrod, the ensemble invited the audience to sing along on the refrain—and they did! And got it mostly right by the fifth or sixth repetition. Sramek noted, in his last remarks, “You have azaleas, and all sorts of things blooming. . . we’re from Minnesota.” The Rose Ensemble sings sacred and secular music spanning a thousand years—from Slavic liturgical music to early American hymns to traditional Hawaiian vocal music to the Mexican Baroque to this program of Sephardic, Christian and Arabic origins—astonishingly, with superb vocal production stylistically unique to each genre. The research that informs their singing is meticulous, but the effect is worth all the effort. This review was originally broadcast on WHRO 90.3 FM’s “From the other side of the Footlights.”

It was the last piece on the program and I expected to be dazzled by my first live performance of Shostakovich’s String Quartet No. 3 in F Major, Op. 73. I was not. Certainly the playing was accurate. I know this because this and the second quartet were my first and oft-repeated experience on LP recordings and so the soundtrack is definitely in my brain. St. Petersburg String Quartet, with pleasing string tones, gave a smoothly integrated sound that was accurate. Being in the room with the players gave me a visceral experience of how the individual voices interact. The role of the violist, Boris Vayner, made the greatest impact for me. Mr. Vayner seemed deeply engaged in the music he was making and communicated it effectively.  Alla Aranovskaya, first violinist and Leonid Shukayev, cello, are founding members of the SPSQ and are very comfortable in their playing. They know this music as well as they know their own faces in the mirror. The excitement is long gone; there is no edge to their performance. I missed the edge. The newest member of the group, second violinist Evgeny Zvonnikov, who joined the ensemble in 2010, has a supporting role here and as such it is difficult for me to evaluate the energy brought to the endeavor. Shostakovich’s music speaks of the edge. Humanity has always struggled with the issues he addresses. It is the concept of “levels” of despair in dance music that we find in Shostakovich. The quartet was mostly written in 1946 after WWII had ended and he at first gave titles to the five movements: “Calm unawareness of the future cataclysm, rumblings of unrest and anticipation, the forces of war unleashed, homage to the dead, the eternal question of Why? and for what.” I suspect that he realized that they were unnecessary and he abandoned the titles. His music holds all of this and can always be applied to current events at any time. The cover of my old LP showed four gangsters with hats pulled low, skulking through the night trying to be as inconspicuous as possible while carrying their instrument cases. It was impossible to remain inconspicuous with Shostakovich’s immense reputation. He could reach millions of minds and this put him in jeopardy. He lived in a country whose leaders took art seriously as a social force. Think of Iranian and Chinese film makers in today’s world. Totalitarian states are afraid of artists because they are hard to control. Come to think of it, so are democracies. The program opened with Franz Schubert’s (1797-1828) Allegro in C minor for String Quartet “Quartettsatz” D703. Written in December 1820, it is lovely lyrical music of great tenderness. There are agitated transitions of intensity. Musical phrases passed from one instrument to the next give a sense that there are several of each creating a breadth of sound. This was followed by a delightful treat, Five Miniatures on Jewish Folk Themes (1989) by Sulkhan Tsintsadze (1925-1991). Tsintsadze was from Georgia, a republic in the Caucasus and part of the U.S.S.R. during most of his lifetime. His first string quartet was written when he was a student. It brought him the Georgian Composers Union Prize in 1947; his second string quartet and a quartet miniature based on folk music also won the prize. The arc of his maturing as a composer can be seen in his twelve string quartets, all the while becoming known for his string quartet miniatures. The piece came late in his career. Feast Song is romantic Russian in flavor. L’Chaim (To Life) is a familiar folk tune as is Tailor’s Song, both used in Fiddler on the Roof. There is a harder edge to the colorist pieces compared to the Broadway version. Lomir Ayle Inem is sung to celebrate a friend. lomir ich iberbeiten (let’s forgive one another) is a square sort of dance tune with lyric music with dramatic agitation that sometimes has a grotesque side. It would be interesting to hear the string quartets by Tsintsadze.

It makes sense that the historic College of William and Mary, which boasts the oldest college building in the United States, would have a thriving Baroque music ensemble. The Wren Masters are a quartet: Sarah Glosson on Baroque cello and viola da gamba; Ruth Van Baak Griffioen, recorders; Thomas Marshall, harpsichord; and Susan Via, Baroque violin.

They led off with what they called “baroque E-Z listening”—William Williams’s onomatopoetic Sonata in Imitation of the Birds. The adagio featured violin, then recorder, chirping away; then a brightly ornamented allegro, then grave. The final dancing allegro movement was cheerful, but not giddy. The beautiful gilt-embellished, double-manual harpsichord was Marshall’s own instrument, a 1983 copy of a 1783 French instrument. Marshall noted that he usually plays the Bach Trio Sonata No. 4 in E minor on the Wren Chapel organ, but transposed it up so that the instruments could reach all the notes. Griffoen added, “That means it takes four of us to do what Tom usually does by himself.” It began with Bachian perpetual motion, with a steady impulsion in the continuo that moved the music forward. The Largo contrasted a slow, “walking” continuo with complicated patterns in the treble, that almost ended in a question mark. Jean Philippe Rameau’s Le Rappel des Oiseaux (Reminder of Birds) was a harpsichord solo by Marshall. Jacob van Eyck’s Engels Nachtegaeltje—English nightingale—was originally an English broadside ballad. Griffioen sang a short bit from it to demonstrate the tune, then noted that the Dutch variations imitated birdsong—which she proceeded to do, with fingers flying, in statements that were echoed lower and softer. The dynamics were dazzling. Violin, viola da gamba and harpsichord presented Sonata II in D Major by Buxtehude, with an adagio of spritely dotted notes, and the viola da gamba’s rich, low notes. An interesting cadence segued into a slower movement. The thoroughly charming Le Rossignol en Amour (The Nightingale in Love), by François Couperin, was a very French nightingale, with wonderful trills and riffs and chuffs by Griffioen on recorder, subtly abetted by harpsichord. Biber’s Rosary Sonata #10: The Crucifixion is part of a collection of sonatas on the life of Christ. The scordatura tuning brought the violin’s E string down to D, with unusual dotted rhythms, increasing in intensity. The cello was plaintive against the violin’s ornamentation and striking technique: suddenly very fast, very busy. The final work on the program was Aria 15 on “The Box of Needles”—a song whose title roughly translates to, “You broke my needle box and now you have to pay for it.” Playing a 17th century recorder, Griffioen whipped through its fast flying notes and cheerful dotted rhythms. Oh—that surprise tie-in for this “Birds and B’s” concert? The name of the last composer was Uccellini—which means “little birds.” This review was originally broadcast on WHRO 90.3 FM’s “From the other side of the Footlights.” Back to Review Index Back to Top Home Calendar Announcements Issues Reviews Articles Contact Us |

Singing from memory throughout, they began with the Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) song, Cuando’l Rey Nimród, a miracle tale of how an evil king’s plan to slaughter the newborn Abraham was thwarted. Introduced by David’s Burk’s ’ud (a lute-like Middle Eastern instrument), tenor Nicholas Chalmers and baritone Jonathan Ten Brink intoned the tale and were joined by Ginna Watson’s vielle (medieval violin) and by the women: sopranos Kim Sueoka, alto Linda Kachelmeier and soprano Nell Snaidas. They transported the audience into an ancient time and culture with arrestingly unusual scale intervals, dazzling vocal technique, and expressive musicianship.

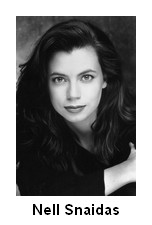

Singing from memory throughout, they began with the Ladino (Judeo-Spanish) song, Cuando’l Rey Nimród, a miracle tale of how an evil king’s plan to slaughter the newborn Abraham was thwarted. Introduced by David’s Burk’s ’ud (a lute-like Middle Eastern instrument), tenor Nicholas Chalmers and baritone Jonathan Ten Brink intoned the tale and were joined by Ginna Watson’s vielle (medieval violin) and by the women: sopranos Kim Sueoka, alto Linda Kachelmeier and soprano Nell Snaidas. They transported the audience into an ancient time and culture with arrestingly unusual scale intervals, dazzling vocal technique, and expressive musicianship. Special guest soprano Nell Snaidas, who specializes in Italian and Spanish Baroque and Sephardic music, has sung all over the world. Accompanied by ’ud and drums, using her heels as subtle percussion, her expressive eyes and subtle physical movements brought to life the traditional Sephardic song Una matica de ruda (A Sprig of Rue), in which a mother asks her daughter, “Who gave you this flower?”

Special guest soprano Nell Snaidas, who specializes in Italian and Spanish Baroque and Sephardic music, has sung all over the world. Accompanied by ’ud and drums, using her heels as subtle percussion, her expressive eyes and subtle physical movements brought to life the traditional Sephardic song Una matica de ruda (A Sprig of Rue), in which a mother asks her daughter, “Who gave you this flower?”  They played April 30 at Virginia Wesleyan College (only 300 years younger than William and Mary) as part of Wesleyan’s excellent concert series. Playfully entitled “The Birds and the B’s,” the program included three selections by Bach, Buxtehude and Biber, four selections inspired by birds—and a surprise tie-in at the end.

They played April 30 at Virginia Wesleyan College (only 300 years younger than William and Mary) as part of Wesleyan’s excellent concert series. Playfully entitled “The Birds and the B’s,” the program included three selections by Bach, Buxtehude and Biber, four selections inspired by birds—and a surprise tie-in at the end.