| Cantus SMSC Finale Concert Led by Bob Chilcott |

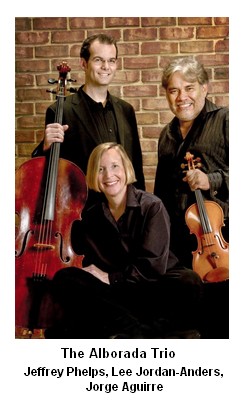

ReviewsThe Alborada Trio’s Homage to Ravel Pianist Lee Jordan-Anders, violinist Jorge Aguirre and cellist Jeffrey Phelps, performing as the Alborada Trio, left the world of pretty Romantic music far behind in a stimulating and enticing program of three works. They opened with Lalo Schifrin’s (b. 1932) Hommage à Ravel (1994) music inspired by early Stravinsky, four movements that explore a palette of sound that is unsettlingly modern. In the Tango movement, at times thorny combinations grab our attention and tweak emotional responses. There is a sadness and longing of painfully measured elongated time in Elégie. The Finale is more lively, a broad spectrum of colors bursting with intensity. It took the great coordinated skill of the players to bring off such overwhelming music. Near the end the solo cello rambles about, picking up threads of violin and piano lines. They unite by the end.

In the late 1950s he could be found in the United States as arranger for Dizzy Gillespie, touring the great concert halls of Europe with his ensemble. Within five years he had established himself as a composer of film and television scores: The Fox, Mission Impossible, Mannix, Cool Hand Luke, some seventy titles altogether. He also continued to compose for the concert hall and symphony orchestra. He wrote Hommage à Ravel in 1994 for the Eaken Piano Trio.

Their performance of the final work, Ravel’s Piano Trio in A Minor (1913), continued the emphasis on his innovative instrumental writing, restoring the edges to his composition. The new effects of color and expression apparent in the first movement, titled Modéré, demonstrated brilliant string techniques: double-octave spacing, harmonics, tremolandi, extended pizzicato and trills. Ravel drew on his mother’s Basque homeland for the first movement folk dance and rhythms. This melodic motive was featured prominently in the later movements, and was inverted in the last. The structure of the second movement, Pantoum: Assez vif (rather brisk), is based on a poetry form. To demonstrate, a translation of Evening Harmony by Charles Beaudelaire was printed on the back of the program. Every second and fourth line is repeated in the next four line stanza. Ravel uses four different thematic groups to replicate the poetic form in music. Passacaille begins with an eight bar melody in the piano’s lowest register, taken up by cello and then violin, each with variations. It builds to a dramatic climax, only to fade away precisely as it began. The animated music of Final: Animé begins without pause. To excite the listener Ravel uses a fantastic metric design that uses asymmetrical patterns of 5/4 and 7/4 complemented by intricate layers of contrapuntal sound. By the end of the performance you knew that you had been in the presence of a modern master and of a trio who made you aware of this fact. In the intimate surroundings of Virginia Wesleyan’s Hofheimer Theater November 22nd, the nine members of the male a cappella group Cantus impressed a knowledgeable audience with their immaculate blend, tight choral sound and excellent musicianship. Their program — “A Place for Us” — explored the diversity that makes up this country. Spoken quotes from poets and authors from Walt Whitman to Langston Hughes and others, highlighted the meaning behind the songs. They asked, “Where is home for you? How do you know where you belong?” Cantus began with “Somewhere,” letting Leonard Bernstein’s arching melody and Stephen Sondheim’s lyrics reach out with longing. One singer stepped forward to speak part of Walt Whitman’s “O Pioneers!” The Finlandia Hymn by Jean Sibelius, which appears in many hymnals, had a fresh, clean sound and seamless crescendos. “Fiddle Tune” (traditional) was very fast, with mesmerizing syncopation and modulations — think scat meets mouth music. A hand drum, the soft sound of brushed hands and rhythmic stamping accompanied “Lakota Wiyanki,” in which declaration was interspersed with “Lakota” in soft whispers, like ghost voices, with superbly tuned dissonances. The singers changed position, sometimes slightly, sometimes more, to ensure the best sound for the particular song.

A guitar accompanied the Appalachian folk song “Pretty Saro,” in which a man can’t forget the love who spurned him for his lack of land. From soloist to duets to the whole group, each verse varied. They quoted Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of committed citizens can change the world,” which led into the traditional American tune, “We Shall Not Be Moved,” with tenor descants and a full, virile sound. The 18th-century choral composer William Billings adapted Psalm 137 as “Anthem: Lamentation over Boston,” which conveyed the bitterness of memory—and its necessity. A wordless hum began the challenging Dave Matthews song, “Gravedigger,” which asks, “Gravedigger, make my grave shallow so that I can feel the rain.” The measured pace of “Paradise” brought out a different emphasis in the lyric. Inuit chants in heterorhythms formed the basis of “Nukapianguaq,” another challenging work in which three groups of three singers, with drum and clapping, sang different chants at the same time, increasing the tempo, varying the dynamics and rhythmic variations. It was . . . astonishing, displaying an incredibly high order of musicianship. “Hole Waimea” began as a traditional Hawaiian name chant, and evolved into modern harmony. The Mexican folk song, “El Pajarito Cu,” was sly fun. “Let America Be America Again” is a poem by the great poet of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes; Cantus tenor Paul Rudoi adapted it as “America Will Be!” The song, beautifully sung, speaks of all who are left out of America’s prosperity, yet rings with hope that America will be what it promises. Hall Johnson’s “Ain’t Got Time to Die,” had wonderful anticipated accents. The Shaker tune “Simple Gifts” and a reprise of “Somewhere” wound up the program. Their encore was Stephen Foster’s evocative “Hard Times Come Again No More.” They omitted one song in the program, “Northwest Passage,” by the late Canadian folk singer Stan Rogers. It’s one of my favorites—but apparently it will be on their next CD. Based in Minneapolis, Cantus has sung all over the country, including a very recent appearance on Prairie Home Companion. They also appeared at the American Theatre on Wednesday, December 4, singing All Is Calm, which recalls the World War I Christmas truce between Allied forces and German soldiers. This review was originally broadcast on WHRO 90.3 FM’s “From the other side of the Footlights.”

The wrap-up of the Virginia Wesleyan College Sacred Music Summer Conference is always a choral program led by a guest conductor and this year was no different. This year it was a compact, one-hour, no-intermission concert with an excellent rapport between singers and conductor performing beautiful music, all sung in English. Several brief, brass fanfares were played, punctuating the quiet chatter while twilight subtly illuminated the stained-glass windows while the moderate-sized audience, who had braved the rain and storm, arrived. The joyful, high-energy of Zadok the Priest (1727) from Handel’s Coronation Anthems opened the program. The massed voices, accompanied by organ, brass and percussion, set the exuberant tone, bringing us into a spirit of celebration. Oxford University Press has published more than 125 pieces by Chilcott and several were included in this concert. Walk Softly, on a Shaker text, drew on the English choral tradition using pauses to emphasize a text of quiet, incandescent fervor. There was a fine organ prelude, played by Kevin Kwan, for the next piece by Chilcott, Thou Knowest Lord, the Secrets of Our Hearts from his Requiem, that enfolds the sadness in a warm, vocal embrace. Organist Kevin Kwan’s keen, nuanced sensitivity on this instrument has won me over. I now look forward to hearing him play. The wistful, pastoral Folk Tune from Five Short Pieces by Percy Whitlock (1903-1946) had memorable melody and rich, harmonic color. The women of the chorus opened Felix Mendelssohn-Bartholdy’s (1809-1847) He, Watching Over Israel (Elijah) and the men’s voices blended on the repeat of the opening text. There was power in the elegantly, understated singing. Bob Chilcott (b. 1955) has written his own St. John Passion for Well’s Cathedral. In this version, like J.S. Bach’s, there is a tenor Evangelist narrator and the role of the choir is as the crowd and a group of soldiers. For the choir and audience Chilcott included five, well-known hymn texts which were sung by the VWC chorus as Five Hymns. The sweet, gentle flow of the music allowed the words to be heard. It is consoling, enfolding, singable music, never harsh and quietly dramatic with some rich, full closings. Sylvia Chapa was advance rehearsal director and soprano core was Billye Brown Youmans and Ann Scott-Davis; altos, Bonnie Lambert-Baxter and Connie Faivre; tenors, Rusty Youmans and John Holman; basses, Steve Kelley and Jeremy Yoder. Local singers, conference participants and singing enthusiasts who returned to the area just to participate made-up the chorus of 95 voices. The brass players were: trumpet, Lawrence Clemens and Wendell Banyay; horn, David Wick; trombone, Mike Hall; tuba, Brad Parrish; timpanist, Tim Bishop. As with the opening piece, they were key to the joyfulness of the last two songs by Ralph Vaughan Williams (1872-1958): O, Clap Your Hands and The Old Hundredth (Psalm 100). The chorus was joined by the audience in three of the five verses. All instrumentalists and all voices joined in the triumphal close. All of this in just one, packed hour! Back to Review Index Back to Top Home Calendar Announcements Issues Reviews Articles Contact Us |

Composer Lalo Schifrin grew up in Buenos Aires , Argentina, listening to his father play violin as the concertmaster of the city’s main opera house. His music education began under Enrique Barenboim (Daniel’s father) at a time when Europe’s greatest conductors and performers visited regularly. As a young man in Paris from 1952 he led a double life attending courses taught by Messiaen and Charles Koechlin by day and frequenting jazz clubs at night.

Composer Lalo Schifrin grew up in Buenos Aires , Argentina, listening to his father play violin as the concertmaster of the city’s main opera house. His music education began under Enrique Barenboim (Daniel’s father) at a time when Europe’s greatest conductors and performers visited regularly. As a young man in Paris from 1952 he led a double life attending courses taught by Messiaen and Charles Koechlin by day and frequenting jazz clubs at night.  In a series of piano works in the first decade of the twentieth-century Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) carried out a kind of velvet revolution, renewing the language of music without disturbing the peace, according to critic and author Alex Ross. In Lee Jordan Anders' illuminating trio arrangement of five pieces from Mother Goose (Ma mere l’oye) originally written for piano duo, the revolutionary aspects were very clear: smooth, somber music of Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty interrupted by squawks of the cello, and the pizzicato strings and twinkling clarion piano in Tom Thumb which gave way to a rather stately dance in Laideronette, Empress of the Pagodas. The lovely string playing in Conversation of the Beauty and the Beast was the voice of Beauty. Intensity builds with piano glissandi at the end. The Fairy Garden gives a feeling of an insatiable lust for life. In this garden men and women taste and feel everything life can offer. Ms. Jordan-Anders’ projected program notes told us that “unmarried and childless, Ravel adored children and their world of fantasy.” Mother Goose draws on the fairy tales of Perrault, as well known then as today.

In a series of piano works in the first decade of the twentieth-century Maurice Ravel (1875-1937) carried out a kind of velvet revolution, renewing the language of music without disturbing the peace, according to critic and author Alex Ross. In Lee Jordan Anders' illuminating trio arrangement of five pieces from Mother Goose (Ma mere l’oye) originally written for piano duo, the revolutionary aspects were very clear: smooth, somber music of Pavane of the Sleeping Beauty interrupted by squawks of the cello, and the pizzicato strings and twinkling clarion piano in Tom Thumb which gave way to a rather stately dance in Laideronette, Empress of the Pagodas. The lovely string playing in Conversation of the Beauty and the Beast was the voice of Beauty. Intensity builds with piano glissandi at the end. The Fairy Garden gives a feeling of an insatiable lust for life. In this garden men and women taste and feel everything life can offer. Ms. Jordan-Anders’ projected program notes told us that “unmarried and childless, Ravel adored children and their world of fantasy.” Mother Goose draws on the fairy tales of Perrault, as well known then as today. The fascinating—and incredibly difficult— “My Journey Yours,” by Elise Witt, was sung in English, Kurdish, Arabic, Mano (Liberia), Amharic (Ethopia), Bosnian, Vietnamese and Somali. Pairs of singers clapped different patterns with their hands at the same time—simultaneous but separate. Different tunes sometimes overlapped; different descants arose. . . it was amazing!

The fascinating—and incredibly difficult— “My Journey Yours,” by Elise Witt, was sung in English, Kurdish, Arabic, Mano (Liberia), Amharic (Ethopia), Bosnian, Vietnamese and Somali. Pairs of singers clapped different patterns with their hands at the same time—simultaneous but separate. Different tunes sometimes overlapped; different descants arose. . . it was amazing! Conductor Bob Chilcott, described as “a contemporary hero of British choral music,” moved both hands like magic wands, inspiring a well-coordinated vocal response in How Lovely Is Thy Dwelling Place by Johannes Brahms from his A German Requiem. The focus of this mass from Psalm 84 is on the living, not the dead and introduces a world of gentleness and tranquility, concluding in a great fugue of rejoicing.

Conductor Bob Chilcott, described as “a contemporary hero of British choral music,” moved both hands like magic wands, inspiring a well-coordinated vocal response in How Lovely Is Thy Dwelling Place by Johannes Brahms from his A German Requiem. The focus of this mass from Psalm 84 is on the living, not the dead and introduces a world of gentleness and tranquility, concluding in a great fugue of rejoicing.  Sun Dance is the final piece from Organ Dances by Chilcott. Kwan plays this music that catches fire, first at the beginning, giving way to deeper tones, always exhilarating with an abrupt end.

Sun Dance is the final piece from Organ Dances by Chilcott. Kwan plays this music that catches fire, first at the beginning, giving way to deeper tones, always exhilarating with an abrupt end.