| Rite of Spring |

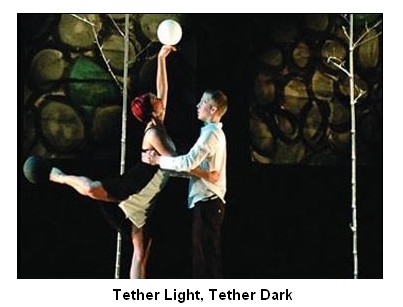

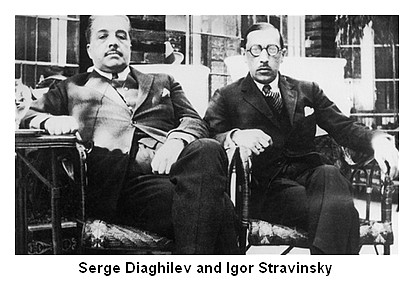

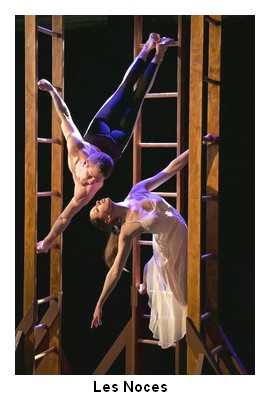

ReviewsTodd Rosenlieb Dance Takes On Igor Stravinsky It was a spectacular evening of entertainment, though when we arrived at Chrysler Hall few in the audience knew what to expect. Les Noces requires a full chorus, four soloists - soprano, alto, tenor and bass, four pianists and an array of percussion. To bring Les Noces to the stage required a community and we are still dazzled by the experience. Seldom performed, who would mount it but a music festival? It is not a symphony; it bends the usual format. Stravinsky broke barriers and expectations: there is no wedding ceremony but there is a narrative of related events. The choreography was a reinvention. Stravinsky challenged our assumptions and in his spirit, Rosenlieb has done the same. The evening was a dance recital with live music. What music it was! Two pieces with music by Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) were featured. Tether Light, Tether Dark was danced to Stravinsky’s Octet, choreographed by Todd Rosenlieb with costumes by Ricardo Melendez performed by VAF Chamber Musicians. After Mother Goose, choreographed and costumed by Mr. Melendez with music by Ravel, Ma Mere L’Oye (Mother Goose Suite for four hands), we saw Les Noces choreographed by Mr. Rosenlieb with costumes by Mr. Melendez and music by Stravinsky.  Tether Light, Tether Dark featured seven dancers with black or white balloons attached to fingers, toes and even used as cover for private parts, all in good fun. As the three movements of Octet unfolded, the busy, whimsical dancing was paired with dazzling playing by Debra Wendells Cross, flute; Patti Ferrell Carlson, clarinet; Laura Leisring & David Savige, bassoon; Matt Ernst & Ryan Barwise, trumpet; Scott McElroy & Rodney Martell, trombone. The dancers were Beth Blachman, Beau Dobson, Jennifer Somers-Heable, Dougals Ruis, Rob Morrow, Melanie Ortt (only danced this piece) and Janelle Spruill. A fairyland of children’s games in bright, solid colored costumes gave visual life to Mother Goose set to the music of Maurice Ravel. André-Michel Schub and Lydia Artymiw were at the piano with Robert Cross, percussion. The dancer ensemble added Abigail Axelrod, Courtney Callaway, Ronald Parker, and Joppa Whitehead.  Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971) was born in Russia, the son of the principle bass at the Imperial Opera, St. Petersburg. He studied law at St. Petersburg University but in 1901 he spent his time at Rimsky-Korsakov’s house pursuing music. Soon Stravinsky was studying with Rimsky-Korsakov full time and wrote his first symphony and piano sonata. In 1909 Diaghilev, who had already established the Ballets Russes in Paris, heard two short works by Stravinsky and invited him to compose a ballet. Firebird was a hit in 1910 and his career was launched. Petrushka followed in 1910/11. The Rite of Spring (1913) completed Stravinsky’s nationalistic phase. In the transition from his nationalistic early ballets to his Neoclassic works he wrote scores for small groups in a pointed, precise way. Roughly from 1918-1923 Stravinsky composed L’Histoire du Soldat, the ballet Renard, a one-act opera Mavra, Symphonies of Wind Instruments and the cantata Les Noces. The Russian title of Les Noces (The Wedding) is “Svadebka” and would be correctly translated “Little Wedding” with a sense of affection implied. In 1914, the year after The Rite of Spring, Stravinsky began writing Svadebka and completed it in 1923 while living in Paris where it came to the stage on 13 June, 1923. The work is written for chorus, four soloists, four pianos, a percussion group that includes xylophone, tympani, antique cymbals, bell, drums, tambourine, bass drum, cymbals, and triangle. The text is based on a collection of popular Russian poems by Kireievsky and described by Stravinsky as “a suite of typical wedding episodes told through quotations of typical talk…clichés and sayings. It might be compared to a scene in [James Joyce’s] Ulysses, in which the reader seems to be overhearing scraps of conversation without the connecting thread of discourse.” The idea of the arranged marriage both delights and scares the bride and groom as they prepare for the ceremony accompanied by family and friends in scenes one and two. In the third scene the bride receives a blessing from her family and the fourth scene is the wedding feast. The wine flows freely and the revelers loosen-up. A married couple warms the newlywed’s bed and the four parents sit outside the door of the bridal chamber as the newlyweds retire. It should be noted that the groom has been sung by the tenor but here we hear the bass.

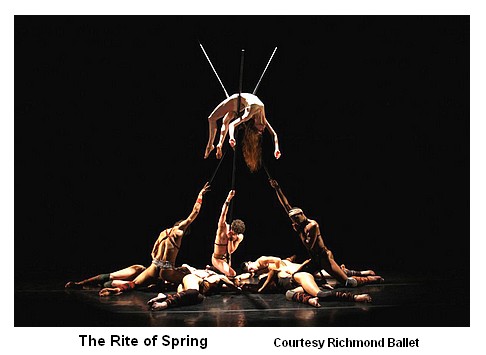

Local composer Richard Moriarty, who watched the London Ballet YouTube performance, wrote that by contrast “what we saw Saturday night was much more intense, sensual and erotic and vibrant. The tension between the women and men dancers was palpable and the male gymnastics left no doubt as to the athleticism of male dancers. I wish the percussion had been more forward on the stage....especially the piano, which occasionally got lost with all the voices...”. Soprano Rebecca Nash had power and stamina in the lead role. Mezzo-soprano Robynne Redmon, tenor Robert Breault and bass Denis Sedov completed the strong vocal quartet. The pianists Schub and Artymiw were joined by Josu de Solaun and Anna Petrova. The percussionists were Tim Bishop, Robert Cross, Mark Hodges, Scott Jackson, Ji Hye Jung, Michael Laubach and Joey Sanchez. The Virginia Symphony Chorus, seventy voices strong, created a mighty but indistinct sound. Conductor JoAnn Falletta handled the diverse forces with a masterful touch. Les Noces was a new piece for most of the Chrysler Hall audience. Native Russian speakers have told us that the chorus’ Russian diction was unclear and the pianists were only approximate in their execution. In Paul Griffiths’ book, Stravinsky, he speaks to both points. Like the original French audience we heard the piece in Russian, a foreign language for them as well as us. Griffiths says “…the omnipresence of the piano tone conveys something of the atmosphere of a rehearsal, so that any performance of Les Noces seems an appeal to an ideal that has still to be achieved.” Enough said. The characters, represented by dancers, do not need singers to embody them. The soprano and bass soloists are fleetingly identified with the bride and groom but they also sing words of the bride’s mother and the best man. Most usually they are caught up into the sound of the chorus. They are not enacting the wedding but reporting across time an event of old Russia to a Western audience. The audience is challenged to understand that what they have experienced is a marriage in many dimensions: of male and female, ancient and modern, ritual and machine, voice and instrument, narrative and action, song and dance. To quote Paul Griffiths “But perhaps its deepest, and most deeply Russian binding is of holiness and humor, the holiness of a ceremony going on beyond the senses and the humor of drunken guests at a wedding party. It is both comedy and icon.”  One hundred years ago, May 29, 1913, Le Sacre du Printemps came to the stage in Paris. The music was by Igor Stravinsky (1882-1971)and the choreography by Vaslav Nijinsky (1890-1950). The near-riot in the theater was in reaction to both music and dance. The choreography was outrageous in its subversion of conventional ballet, danced to Stravinsky’s rhythmically complex score, heard as barbaric noise. On March 7, 1912, as Stravinsky was writing his new piece, Vesna syash-chennaya in Russian and Rite of Spring in English, Stravinsky wrote to Andrey Rimsky-Korsakov (composer Nikolai’s son): “It is as if twenty and not two years have passed since I wrote the Firebird. The music is coming out fresh and new” (Stravinsky by Paul Griffiths, pg. 28). The music had a primitive old Russian sound (pre-Christian) and was radically new—his current colleagues were Bartók and Schoenberg. I recall that the dancers wore heavy floor-length robes of rough, dull fabric when the Joffrey Ballet appeared in Chrysler Hall in 1988 in a reconstructed staging by Millicent Hudson of Nijinsky’s original choreography. What we saw this time was energetic, 1993 choreography by Salvatore Aiello who became artistic director of North Carolina Dance Theater in 1985. Monica Kane Cunningham with Linda Linsay designed the costumes. Wearing thongs of rich colors with short blouses added for women, the sensual movement of beautiful, young bodies was breathtaking. The Virginia Symphony played with verve and the coordination with the dancing so perfect that it would have been easy to forget that the music was live.  Local choral singer Scott Strickland shared that his favorite male dancer was Fernando Sabino. “I felt his skill shown the brightest. My favorite female dancer was Valerie Tellman, ‘The Chosen One’! She brought such noticeable intensity to her role, which was no small feat in an evening of charged performances. Even though she was the sacrifice, I found her intensity absolutely frightening!” The opening dance piece, Solo in Nine Parts (premiered in 2010), featured the Virginia Symphony in music by Antonio Vivaldi with dance choreographed by Jessica Lang. Costume design was by Tamara Cobus with lighting by MK Stewart. The dancing was closely tied to the bouncy, happy music of Vivaldi. Nine dancers made up the ensemble: five women—Cody Beaton, Lauren Fagone, Maggie Small, Valerie Tellman and Cecile Tuzii and four men—Trevor Davis, Matthew Frain, Thomas Ragland Ariel Rose danced the fragments of Vivaldi's music. Recently added to the Richmond Ballet repertory, the piece premiered November 1, 2012. In 1931 Stravinsky and violinist Samuel Dushkin were touring as a piano/violin duo and the composer was adding to their repertory between gigs. On July 15 he completed the Duo Concertant. This is not a grand, bravura display piece but rather the possibility of conversation. Shira Lanyi and Fernnando Sabino danced Stravinsky’s Duo Concertant. Maria Yefimova was pianist and Ross Winter, violinist. The choreography, created by George Balanchine, was premiered in 1972 by New York City Ballet. Balanchine defected from the Soviet Union after studying at the Imperial Theater in St. Petersburg. In 1925 he succeeded Nijinsky at the Ballets Russes in Paris. In 1934 he directed what, in 1948, became the New York City Ballet. The dancing is very athletic and with energy but the movement is abstract, detached from the music except for its timing. The feeling is austere, fragmented and calculated. Printer Friendly Format

|