| 45th Anniversary Concert |

ReviewsNorfolk Chamber Consort:

The ensemble opened with three pieces by W.A. Mozart (1756-1791), arranged by Michael Hasel, the group’s flutist. The three pieces were written by Mozart for mechanical organ and "cried out for a quintet arrangement with due stylistic sensitivity” says Hasel. “The instruments (except for the horn) are used in accordance with the custom and technical capabilities of Mozart’s era.” All were written from December to May in the last year of Mozart’s life. Andreas Wittman on oboe, Walter Seyfarth, clarinet, Fergus McWilliams, horn, and Marion Reinhard, bassoon, joined in to bring this music to life. These music box transcriptions were wonderfully well played, giving each individual a chance to shine while ensemble playing was superb. The striking quality of the next piece, Quintet for Winds, Op. 10 (1929) by Pavel Haas (1899-1944), demonstrated how much the instrumental sound had changed in the 140 years since Mozart. The same instruments but the interplay of color combinations, more diverse rhythms and the expansion of sounds the player can produce were all visible here in the Preludio. The second movement, Preghiera (Prayer), offers a flute solo that creates an open feeling. Joined by the other players, the oboe is prominent. A jazzy interplay, a clarinet solo, all together now, the bassoon rocks out, back to oboe and now the horn is featured. The Ballo eccentrico, third movement, begins with a bassoon skipping along, joined by clarinet and flute as the piece widens out. It all seems improvised and is moving very quickly. Now the tempo drags as if it is mocking itself, only to speed-up, going even faster in a frenzied folk dance to end. The Epilogo, fourth movement, is serious, even ponderous, with slow tempos and a tight interplay of tones. A rich, full sound develops and becomes edgy, as if it is about to disintegrate, only to conclude in a sweet resolve. This work is a real find. Haas was born in Brno, Moravia (now the Czech Republic) in 1899 and died in Auschwitz in 1944. For the previous two years he was in Terezin concentration camp with a number of other doomed Jewish composers, musicians, playwrights, actors and other artists. It is long overdue that his work be better known and appreciated for its excellence. The second half of the program was devoted to hearty performances of French repertory. Jacques Ibert (1890-1962) Trois pieces brèves (1930), Allegro was a bright, high-stepping dance with all players fully engaged throughout. The second movement has a gentle, pastoral opening with mellow flute solo soon joined by clarinet and later oboe while the horn and bassoon sustain a warm bass drone. The final movement, Assez lent – Allegro scherzando, has a big dramatic opening with sparkling sonorities. It is tuneful and fast with a mellow, clarinet prominent. The music slows briefly only to gather energy for a mad rush. It was such fun and over far too quickly. Darius Milhaud (1892-1974) was a native of Aix–en-Provence where King René’s fifteenth-century court and castle were located. La Cheminée du Roi René, Op. 205 (1939) (King René’s Chimney) derives from music written for the film “Cavalcade d’Amour.” The seven movements with French titles given in the program booklet are, in English: Procession, Morning Serenade, Jugglers, La Maousinglade (local nickname for a topsy-turvy section of the capital city), Jousts on the Arc, Hunting at Valabre and Madrigal-Nocturne, each lasting from one to three minutes. As played, this suite is a single, uninterrupted work. It is easy to conjure a scenario of traveling over hilly countryside, crossing a rushing stream or hearing a folkdance in the distance. “La Maousinglade” with its gentle, swaying oboe sound wraps around the rhythm of the other players. There is Renaissance-style ornamentation in the joust and the hint of a hunting horn in the hunt scene with a marching sort of frolic between the clarinet and bassoon. The pensive and strongly neoclassical Madrigal brings it all to a quiet and restful close.

The opening of the first movement was mighty. Wildly they tore into music that was engaging but not pretty. The bassoon leads into a crisp, treble, cabaret piano solo with colors added by flute, clarinet and horn and later by oboe. It is exhilarating, fast and soon over—a rich dessert for the ears and mind. In the second movement, Divertissement, the piano provides the perfect base for the light-hearted excursions of the winds. The big, boisterous Finale has attitude—a satire on ordinary sonorities with a crazy waltz that provokes at laugh inside me. A moment to breathe and then a soulful bassoon is joined by the other winds with a steady pulse in the piano and an intense conclusion. In the right interpretative hands this work can exude French wit as well as a degree of emotional depth. The brilliance of the virtuosic playing of the Germanic Berliners was exhilarating and felt valid in its own way and the pianist went with their flow. The encore was Les petits nerveux by Jean Françaix, a stunning showpiece for wind quintet and piano. From the beginning the quick tempos accelerated to a dramatic ending.

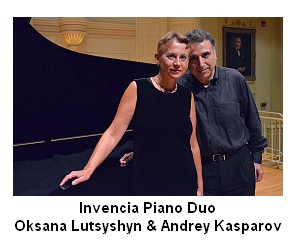

We enjoyed an anniversary cake and a smashingly good reception after we heard a program at Chandler Hall (NCC’s most frequent, recent venue) that was representative of forty-five years of live chamber music presented by Norfolk Chamber Consort. Music by Bach, Mozart and Brahms in the first section was followed by twentieth-century music by Martinů and Britten. The program closed with a showpiece for two pianos by Franz Liszt, recently arranged by Dr. Kasparov and played by Invencia Piano Duo—Andrey Kasparov and Oksana Lutsyshyn, NCC artistic co-directors.

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) Piano Quartet in G minor, Op. 25 (1856-1861) was the first of Brahms chamber works that Brahms played in public. The quartet looks back to Schubert in its sweetness and paves the way toward Schoenberg in Brahms treatment of form, tonality and technique of developing variation. The trio of performers from the Bach/Mozart pieces was joined by the piano of Andrey Kasparov. The Allegro, first movement has the sweetness of heroic themes in repose but it also simmers with tension of a voluptuous richness. The Intermezzo, second movement is introspective. Themes are developed, searching for beautiful and mysterious effects. The ending has a stunning intensity with all four voices fully engaged. The Andante movement was cooler than the first two but still loaded with passion. Here the piano sound opened out like a spring flower on a sunny afternoon. The last movement is a Rondo in the Gypsy style. The percussive piano and the near crying strings combine in pure fire, blasting through rousing themes, thus uniting the audience in a great outburst of applause as the music ends. The Adagio is relaxed, like strolling in a garden on a warm, spring evening near a fountain. Plucked violin strings harmonized with the plucked harpsichord sound in the Scherzando with brief flute phrases rushing about. There is humor in the ending. The urgency in the last movement is not so very serious. The feeling is of bees chasing each other in a noonday meadow and we were there listening.

Any gala anniversary program demands a grand finale and Andrey Kasparov willingly complied by arranging Franz Liszt (1811-1886) Totentanz (Dance of Death) for the two pianos of Invencia Piano Duo (Kasparov and Lutsyshyn). Liszt wrote two versions of Totentanz for piano and orchestra and one for solo piano. In addition he transcribed the orchestral part for a second piano. Kasparov shaped the piece, retaining the opening, crashing, dark chords of Liszt’s second orchestral version over the Dies Irae of the Requiem Mass followed by six variations. The new version by Kasparov equally distributes the music between the two players. Back to Top

|

As part of Old Dominion University’s Diehn Concert Series, the Berlin Philharmonic Wind Quintet played for a full house in Chandler Hall on February 17, 2014 in a program that featured twentieth-century music and Mozart. The quintet, formed in 1988 during the era of conductor Herbert von Karajan, has four original members. The BPWQ is committed to wind quintet repertoire and in 1991 partnered with BIS Records to record “definitive” or “reference” performances.

As part of Old Dominion University’s Diehn Concert Series, the Berlin Philharmonic Wind Quintet played for a full house in Chandler Hall on February 17, 2014 in a program that featured twentieth-century music and Mozart. The quintet, formed in 1988 during the era of conductor Herbert von Karajan, has four original members. The BPWQ is committed to wind quintet repertoire and in 1991 partnered with BIS Records to record “definitive” or “reference” performances. The closing piece was Sextet for Piano and Wind Quintet, Op. 100 (1932-1939) by Francis Poulenc (1899-1963). Andrey Kasparov, co-director of Norfolk Chamber Consort, on piano, joined the winds. NCC listeners heard the Poulenc Sextet last season with Pianist Oksana Lutsyshyn, NCC co-director, with Windscape wind quintet. Indeed, it is one of Poulenc’s most popular works.

The closing piece was Sextet for Piano and Wind Quintet, Op. 100 (1932-1939) by Francis Poulenc (1899-1963). Andrey Kasparov, co-director of Norfolk Chamber Consort, on piano, joined the winds. NCC listeners heard the Poulenc Sextet last season with Pianist Oksana Lutsyshyn, NCC co-director, with Windscape wind quintet. Indeed, it is one of Poulenc’s most popular works.  Things got off to a slow, quiet start as former Artistic Co-Director Allen Shaffer played two Bach preludes and fugues interspersed with Mozart’s arrangements for string trio of the Bach pieces. Personally I have a life-long connection of listening again and again to the Mozart/Bach pieces on an LP recording (c.1966). The music is not quite Bach, not quite Mozart but an intriguing hybrid. The cool, tinny tinkle of the harpsichord is transformed into the richness of blended strings. After it got through a tentative opening, the prominent violin sang sweetly. Mozart arranged the Bach for noon matinees at a nobleman’s home. The informal gatherings featured music by both Bach and Handel. We heard Mozart’s arrangements from Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier, Book 2. Bach's Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp major became Mozart's Prelude and Fugue No. 3 in F major, K.404a. The key change was necessary for ease in playing on stringed instruments. Likewise, Bach's Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp minor became Mozart's Prelude and Fugue No. 2 in G minor. Individual voices of the strings, violinist Pavel Ilyashov, violist Satoko Rickenbacker and cellist Jeffrey Phelps, were striking. Later the sound blended into a beautiful richness.

Things got off to a slow, quiet start as former Artistic Co-Director Allen Shaffer played two Bach preludes and fugues interspersed with Mozart’s arrangements for string trio of the Bach pieces. Personally I have a life-long connection of listening again and again to the Mozart/Bach pieces on an LP recording (c.1966). The music is not quite Bach, not quite Mozart but an intriguing hybrid. The cool, tinny tinkle of the harpsichord is transformed into the richness of blended strings. After it got through a tentative opening, the prominent violin sang sweetly. Mozart arranged the Bach for noon matinees at a nobleman’s home. The informal gatherings featured music by both Bach and Handel. We heard Mozart’s arrangements from Bach’s Well Tempered Clavier, Book 2. Bach's Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp major became Mozart's Prelude and Fugue No. 3 in F major, K.404a. The key change was necessary for ease in playing on stringed instruments. Likewise, Bach's Prelude and Fugue in F-sharp minor became Mozart's Prelude and Fugue No. 2 in G minor. Individual voices of the strings, violinist Pavel Ilyashov, violist Satoko Rickenbacker and cellist Jeffrey Phelps, were striking. Later the sound blended into a beautiful richness. After Intermission we heard Promenades H.274 (1939) by Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959). Martinů was a Czech composer who moved to Paris in 1923 and studied with Roussel. He eventually came to the United States in 1941 where he composed his five symphonies. A prolific composer (400 compositions), his works are full of rhythmic energy and imagination. Often performed on piano, Oksana Lutsyshyn played the harpsichord with Bokyung Kim on flute and Mr. Ilyashov on violin. The four brief movements have an insubstantial, surreal flavor— the bite and piquancy of a Baroque harpsichord combined with a 20th-century palette, offering wit and joy.

After Intermission we heard Promenades H.274 (1939) by Bohuslav Martinů (1890-1959). Martinů was a Czech composer who moved to Paris in 1923 and studied with Roussel. He eventually came to the United States in 1941 where he composed his five symphonies. A prolific composer (400 compositions), his works are full of rhythmic energy and imagination. Often performed on piano, Oksana Lutsyshyn played the harpsichord with Bokyung Kim on flute and Mr. Ilyashov on violin. The four brief movements have an insubstantial, surreal flavor— the bite and piquancy of a Baroque harpsichord combined with a 20th-century palette, offering wit and joy. Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) wrote Abraham and Isaac Op. 51 in 1952 as Canticle II, one of a five-part series of Canticles. Here he sets an ancient Chester Miracle Play text: God demands that Abraham sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. God is seeking complete obedience from his servant. Abraham’s willingness to comply unfolds as a vocal drama for son (sung by countertenor Chris Dudley in the high, reedy voice of a child) and father (the rich, tenor voice of Brian Nedvin). For a quarter of an hour the music’s mysteriously coiled-up emotional force holds the listener in an undiminished tension. The flowing interchange of recitative, arioso and duet are most moving in duet passages when one voice takes over from the other.

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) wrote Abraham and Isaac Op. 51 in 1952 as Canticle II, one of a five-part series of Canticles. Here he sets an ancient Chester Miracle Play text: God demands that Abraham sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. God is seeking complete obedience from his servant. Abraham’s willingness to comply unfolds as a vocal drama for son (sung by countertenor Chris Dudley in the high, reedy voice of a child) and father (the rich, tenor voice of Brian Nedvin). For a quarter of an hour the music’s mysteriously coiled-up emotional force holds the listener in an undiminished tension. The flowing interchange of recitative, arioso and duet are most moving in duet passages when one voice takes over from the other. The emotionally unsettling opening treble duet as the voice of God always challenges the listener to make sense of the meaning of this story. This is the third time I have heard this live and I understood it differently this time. Has mankind created its gods to codify the irrationality of our own nature? The utter vulnerability of a sentient human in the face of events that he cannot control is addressed in this story. The performance was superb. Mr. Dudley, who sang his first performance of Isaac here with NCC in 2009, has since performed it some thirty times. Dr. Nedvin, who is a Jewish Cantor, sang it here for the first time but brought a deep understanding to the text.

The emotionally unsettling opening treble duet as the voice of God always challenges the listener to make sense of the meaning of this story. This is the third time I have heard this live and I understood it differently this time. Has mankind created its gods to codify the irrationality of our own nature? The utter vulnerability of a sentient human in the face of events that he cannot control is addressed in this story. The performance was superb. Mr. Dudley, who sang his first performance of Isaac here with NCC in 2009, has since performed it some thirty times. Dr. Nedvin, who is a Jewish Cantor, sang it here for the first time but brought a deep understanding to the text. Ignoring the stated theme of death, I heard it as a huge argument between Mr. & Mrs. Kasparov that settled into a quiet piano normalcy. A march develops with excesses of loud glissandi and the tempest ended with two pianos still standing, playing quietly a flowing, liquid duet—very pretty and peaceful. But peace cannot last. There is a jump into wild pianism and then a peaceful, hymn-like section. The spectacular close is jarringly percussive with great bombast. It is said that this ending is more dramatic and effective than any of Liszt’s other orchestral piano pieces. Certainly the cheers of the audience saw it as a very grand finale to 45 years of engaging chamber music.

Ignoring the stated theme of death, I heard it as a huge argument between Mr. & Mrs. Kasparov that settled into a quiet piano normalcy. A march develops with excesses of loud glissandi and the tempest ended with two pianos still standing, playing quietly a flowing, liquid duet—very pretty and peaceful. But peace cannot last. There is a jump into wild pianism and then a peaceful, hymn-like section. The spectacular close is jarringly percussive with great bombast. It is said that this ending is more dramatic and effective than any of Liszt’s other orchestral piano pieces. Certainly the cheers of the audience saw it as a very grand finale to 45 years of engaging chamber music.