Amy and Scott Williamson’s Superb Art Song Recital

Opening the Virgina Wesleyan College 2009-2010 Concert Series soprano Amy Cofield Williamson and tenor Scott Williamson with pianist Charles Woodward presented “Songs of the Soul," a dozen settings of poetry by Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman by composers Lee Hoiby (b.1926), John Duke (1899-1984), Kurt Weill (1900-1950), Jake Heggie (b.1961) and locally based Adolphus Hailstork (b.1941) and John Dixon (b.1957).

The opening, a set of Dickinson poems, began with I Shall Not Live in Vain by Heggie. This vocal showpiece for soprano with lots of accidentals in the piano was glorious to hear. Next came a friendly setting of My River Runs to Thee by Dixon followed by a ravishingly beautiful I Shall Keep Singing by Hailstork. It begins with many vocalise passages before and after the text, all with the feel of spiritual depth. Our soprano and the song seem made for each other, though in conversation with Dr. Hailstork we learned that this was the first time he had heard the song with piano accompaniment. I Shall Keep Singing serves as introduction to a nine-song cycle titled Summer . Life . Song March 2004 written for the Ritz Chamber ensemble of Florida. The opening, a set of Dickinson poems, began with I Shall Not Live in Vain by Heggie. This vocal showpiece for soprano with lots of accidentals in the piano was glorious to hear. Next came a friendly setting of My River Runs to Thee by Dixon followed by a ravishingly beautiful I Shall Keep Singing by Hailstork. It begins with many vocalise passages before and after the text, all with the feel of spiritual depth. Our soprano and the song seem made for each other, though in conversation with Dr. Hailstork we learned that this was the first time he had heard the song with piano accompaniment. I Shall Keep Singing serves as introduction to a nine-song cycle titled Summer . Life . Song March 2004 written for the Ritz Chamber ensemble of Florida.

Whitman poems set by Weill and sung by tenor Scott Williamson spoke of Whitman’s being a battlefield nurse during the civil war. The subject of the two poems captures great compassion: O Captain! My Captain - the war is over but President Abe Lincoln lies dead on the deck of the ship of state; Dirge for Two Veterans is the story of a father and son who both fall in the same battle which Whitman says “... the strong dead-march encourages me.” The moon gives light, bugles and drums give music and the poet's heart gives them love. The performance left no room to doubt this deep, sad love.

Three of the six poems by Emily Dickinson set by John Duke: Good Morning - Midnight, a whimsical child’s song with a bluesy ending; Heart! We will forget him! with its wild torrent of piano notes and the intensity of the singer, a wounded woman; and Nobody Knows this Little Rose, a sweet reflection on a simple life, were exceptionally well communicated to us by Amy Williamson.

In The Shining Place (formerly called Four Dickinson Songs) by Hoiby our tenor presented serious, somber explorations by the poet and illuminated by the composer. A Letter is a plea couched in a polite, light-hearted way but states her desire to be aided in the search for self-realization. How the Waters Closed Above Him is a painful, sad song. Wild Nights has a continuous melody of many brief notes and a stentorian energy that continues in There Came a Wind Like a Bugle. Operatic in style with a rumbling, big piano sound, the exciting, possibly destructive wind storm described “How much can come, and much can go and yet abide the world.” This phrase, repeated powerfully three times and the fourth firm and quiet leaves us feeling the storm has passed.

Afer intermission a duet written by Robert Schumann (1810-1856), In der Nacht, began a set of European songs and arias. The blend of voices in this beautiful, romantic but sad song was followed by Gustav Mahler (1860-1911) Wo die schönen Trompeten blase. In a dream the woman hears her lover knocking, asking to come in to be with her. She is happy to agree and reaches for him, only to rouse and hear the nightingale sing and realizes that he is where the trumpets blow in his house of green grass. Mr. Woodward created a virtual orchestra on the piano.

Amy Cofield Williamson wove a web of gossamer silk around our heart until it broke for pity for Tosca’s plight as she sang Vissi d’arte by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924). The beauty Scott Williamson created in E lucevan le stelle could squeeze a tear from a stone. Bravo to both. It was a major coup to open the VWC concert series on September 11, 2009 at Hofheimer Theater with this excellent vocal couple who closed the concert with an extensive dialogue from Un Ballo in Maschera by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). Amelia, who is married to the king, speaks with the king’s best friend Ricardo. With great caution in their words they finally express their love for each other. A tragic end is inevitable. Amy Cofield Williamson wove a web of gossamer silk around our heart until it broke for pity for Tosca’s plight as she sang Vissi d’arte by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924). The beauty Scott Williamson created in E lucevan le stelle could squeeze a tear from a stone. Bravo to both. It was a major coup to open the VWC concert series on September 11, 2009 at Hofheimer Theater with this excellent vocal couple who closed the concert with an extensive dialogue from Un Ballo in Maschera by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). Amelia, who is married to the king, speaks with the king’s best friend Ricardo. With great caution in their words they finally express their love for each other. A tragic end is inevitable.

New Piano Trio Seeks a Name

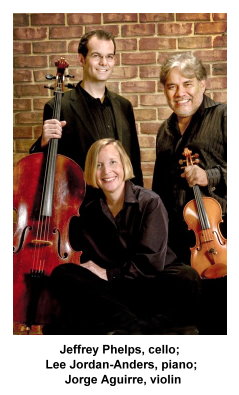

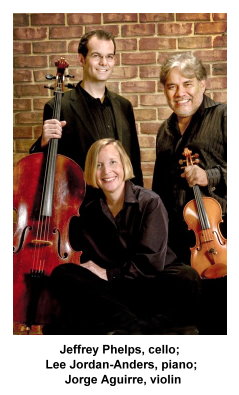

Hofheimer Theater, Virginia Wesleyan College, November 2, 2009. Pianist Lee Jordan-Anders and violinist Jorge Aguirre have performed as Duo Jota-A for several years. Cellist Jeffrey Phelps has joined them in a trio and they are looking for a name for the newly formed ensemble. Ms. Jordan-Anders is Batten Professor of Music and Artist-in-Residence at Virginia Wesleyan and is the newly appointed music director for the Symphony of the Eastern Shore. Jeffrey Phelps is the conductor of the Governor’s School for the Arts orchestra and Mr. Aguirre is a long time member of the Virginia Symphony. Hofheimer Theater, Virginia Wesleyan College, November 2, 2009. Pianist Lee Jordan-Anders and violinist Jorge Aguirre have performed as Duo Jota-A for several years. Cellist Jeffrey Phelps has joined them in a trio and they are looking for a name for the newly formed ensemble. Ms. Jordan-Anders is Batten Professor of Music and Artist-in-Residence at Virginia Wesleyan and is the newly appointed music director for the Symphony of the Eastern Shore. Jeffrey Phelps is the conductor of the Governor’s School for the Arts orchestra and Mr. Aguirre is a long time member of the Virginia Symphony.

Ms. Jordan-Anders gave a spoken introduction to the three works on the program designed as a brief survey of one-hundred years of piano trio development. The piano trio as we know it today developed out of the Baroque duo and trio sonatas. The keyboard - harpsichord - provided the figured bass for strings. In some of J.S. Bach’s sonatas the texture is one of three equally important parts, two of them carried by the harpsichord. Late in his life (1795-1797) Franz Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) wrote three trios for piano, violin and cello which were published in 1970 as part of the first complete edition of his works. The mood of Trio in C Major, HXV 27 is playful and childlike with three, short movements. The lively, charming allegro is followed by a gentle andante that has a soft flow of sound. The finale is marked presto. The importance of the piece in the development of the string trio is that it was written specifically for piano though the cello is given little to do except enrich the piano line.

The second selection, Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Adagio in E-flat Major, “Notturno” Opus post. 148, D 897 was the high point of the concert for me. After Hayden, Beethoven (1770-1827) established the model for chamber music works and Schubert followed his design in two piano trios. The “Notturno” (1827) seems to be a second or third movement that never got used in a three part trio. Lucky for us listeners it is an often played gem. The strings often play together while the piano gets to go its own way, punctuating the conversation between violin and cello. When the piano takes the lead, pizzicato strings offer spice to emotionally expressive music of rare beauty. The performers gave us a comfortable, sensuous experience, leading us into a certain sense of rapture.

The final piece in this 65 minute, continuous concert (no intermission, no printed program (a PowerPoint projection above the performers gave basic information) was Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) B Major Piano Trio. In 1854 the raw genius of a young man was expressed in this string trio, only to be revisited and tempered by the mature composer 35 years later. The rich, full-bodied sound never abates. It is each player for himself. The cello and piano open the Allegro con brio movement, later joined by violin. Three strong but separate voices are all very assertive. Tphe Scherzo, Allegro molto movement has a mysterious short figure that is passed from one instrument to the next. The composer seems to be having fun. The Adagio third movement is somber with a forbidding repeated figure in the piano creating a ponderous feeling. Later the piano accompanies a lyrical passage in the cello creating great beauty. Now, both strings play together. In the Allegro movement the cello is used as a string bass with a soulful, deepened tone while the piano tones leap about. The violin adds top notes to the cello line - all very engaging. The four movement form gives the work a near-symphonic scope which lasted about 40 minutes.

The winner in naming the group will be awarded artisanal food by each performer and free tickets to the trio’s performances forever.

An Evening of Drumming and Chant

Featuring the Poetry of Langston Hughes

On February 12, 2010 at Hofheimer Theater on the campus of Virginia Wesleyan College the stage was laid out with an array of exotic percussion instruments, a drum set and a microphone. The duo, Word Beat, featuring the vocals of Charles Williams and percussion of Tom Teasley, was about to bring us into a world built around the poetry of the African-American genius Langston Hughes (1901-1961). A major voice of the Harlem Renaissance, Hughes captured the essence of the Negro experience of living in America before and during the civil rights movement.

In a rich, deep, resonant voice, Charles Wilson opened with a welcome song by James Welton Johnson punctuated by percussion effects by Tom Teasley who bills himself as a modern percussionist from ancient traditions.

As a followup to the evening I spent most of the following Saturday with my copy of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes published by Vintage and edited by Arnold Rampersad. Mr. Williams recited the first poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, prompted by a train trip west to see his father and published when Hughes was 19 in W.E.B. Du Bois' Crisis magazine. Du Bois gave voice to the life of Negroes in the U.S. in that time (1921) and offered a political critique of how it needed to change. Hughes created poetry that showcased the beauty of African-Americans and the pain of their American experience, expressing emotions, thoughts and dreams that are common to all human beings. I reread the poems we heard recited: Dreams, Hold Fast to Dreams, I Dream a World, I Play it Cool, Acceptance and Evil. In these brief poems Hughes uses deceptively simple words to express feelings that are deep and insights that are often profound. As a followup to the evening I spent most of the following Saturday with my copy of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes published by Vintage and edited by Arnold Rampersad. Mr. Williams recited the first poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, prompted by a train trip west to see his father and published when Hughes was 19 in W.E.B. Du Bois' Crisis magazine. Du Bois gave voice to the life of Negroes in the U.S. in that time (1921) and offered a political critique of how it needed to change. Hughes created poetry that showcased the beauty of African-Americans and the pain of their American experience, expressing emotions, thoughts and dreams that are common to all human beings. I reread the poems we heard recited: Dreams, Hold Fast to Dreams, I Dream a World, I Play it Cool, Acceptance and Evil. In these brief poems Hughes uses deceptively simple words to express feelings that are deep and insights that are often profound.

The solo drum pieces were interspersed with poetry and spirituals and a recitation of selections from Martin Luther King's Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech, “I Still Believe.” Accompanied by Mr. Teasley on the mouth piano, Hughes' poem Mother to Son, with the line “Life ain't been no crystal stair,” encourages the young man to keep climbing upward. Tom-toms in Dance African brought the program to a wild end.

The program was amplified and loud; their sound could fill an auditorium and often does. I would have preferred that they adjust the volume when they play in small, intimate spaces like Hofheimer Theater.

Printer-friendly format

More Virginia Wesleyan

Back to Review Index

Back

to Top

Home

Calendar

Announcements

Issues

Reviews

Articles

Contact

Us |

The opening, a set of Dickinson poems, began with I Shall Not Live in Vain by Heggie. This vocal showpiece for soprano with lots of accidentals in the piano was glorious to hear. Next came a friendly setting of My River Runs to Thee by Dixon followed by a ravishingly beautiful I Shall Keep Singing by Hailstork. It begins with many vocalise passages before and after the text, all with the feel of spiritual depth. Our soprano and the song seem made for each other, though in conversation with Dr. Hailstork we learned that this was the first time he had heard the song with piano accompaniment. I Shall Keep Singing serves as introduction to a nine-song cycle titled Summer . Life . Song March 2004 written for the Ritz Chamber ensemble of Florida.

The opening, a set of Dickinson poems, began with I Shall Not Live in Vain by Heggie. This vocal showpiece for soprano with lots of accidentals in the piano was glorious to hear. Next came a friendly setting of My River Runs to Thee by Dixon followed by a ravishingly beautiful I Shall Keep Singing by Hailstork. It begins with many vocalise passages before and after the text, all with the feel of spiritual depth. Our soprano and the song seem made for each other, though in conversation with Dr. Hailstork we learned that this was the first time he had heard the song with piano accompaniment. I Shall Keep Singing serves as introduction to a nine-song cycle titled Summer . Life . Song March 2004 written for the Ritz Chamber ensemble of Florida. Amy Cofield Williamson wove a web of gossamer silk around our heart until it broke for pity for Tosca’s plight as she sang Vissi d’arte by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924). The beauty Scott Williamson created in E lucevan le stelle could squeeze a tear from a stone. Bravo to both. It was a major coup to open the VWC concert series on September 11, 2009 at Hofheimer Theater with this excellent vocal couple who closed the concert with an extensive dialogue from Un Ballo in Maschera by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). Amelia, who is married to the king, speaks with the king’s best friend Ricardo. With great caution in their words they finally express their love for each other. A tragic end is inevitable.

Amy Cofield Williamson wove a web of gossamer silk around our heart until it broke for pity for Tosca’s plight as she sang Vissi d’arte by Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924). The beauty Scott Williamson created in E lucevan le stelle could squeeze a tear from a stone. Bravo to both. It was a major coup to open the VWC concert series on September 11, 2009 at Hofheimer Theater with this excellent vocal couple who closed the concert with an extensive dialogue from Un Ballo in Maschera by Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901). Amelia, who is married to the king, speaks with the king’s best friend Ricardo. With great caution in their words they finally express their love for each other. A tragic end is inevitable. Hofheimer Theater, Virginia Wesleyan College, November 2, 2009. Pianist Lee Jordan-Anders and violinist Jorge Aguirre have performed as Duo Jota-A for several years. Cellist Jeffrey Phelps has joined them in a trio and they are looking for a name for the newly formed ensemble. Ms. Jordan-Anders is Batten Professor of Music and Artist-in-Residence at Virginia Wesleyan and is the newly appointed music director for the Symphony of the Eastern Shore. Jeffrey Phelps is the conductor of the Governor’s School for the Arts orchestra and Mr. Aguirre is a long time member of the Virginia Symphony.

Hofheimer Theater, Virginia Wesleyan College, November 2, 2009. Pianist Lee Jordan-Anders and violinist Jorge Aguirre have performed as Duo Jota-A for several years. Cellist Jeffrey Phelps has joined them in a trio and they are looking for a name for the newly formed ensemble. Ms. Jordan-Anders is Batten Professor of Music and Artist-in-Residence at Virginia Wesleyan and is the newly appointed music director for the Symphony of the Eastern Shore. Jeffrey Phelps is the conductor of the Governor’s School for the Arts orchestra and Mr. Aguirre is a long time member of the Virginia Symphony. As a followup to the evening I spent most of the following Saturday with my copy of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes published by Vintage and edited by Arnold Rampersad. Mr. Williams recited the first poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, prompted by a train trip west to see his father and published when Hughes was 19 in W.E.B. Du Bois' Crisis magazine. Du Bois gave voice to the life of Negroes in the U.S. in that time (1921) and offered a political critique of how it needed to change. Hughes created poetry that showcased the beauty of African-Americans and the pain of their American experience, expressing emotions, thoughts and dreams that are common to all human beings. I reread the poems we heard recited: Dreams, Hold Fast to Dreams, I Dream a World, I Play it Cool, Acceptance and Evil. In these brief poems Hughes uses deceptively simple words to express feelings that are deep and insights that are often profound.

As a followup to the evening I spent most of the following Saturday with my copy of The Collected Works of Langston Hughes published by Vintage and edited by Arnold Rampersad. Mr. Williams recited the first poem, The Negro Speaks of Rivers, prompted by a train trip west to see his father and published when Hughes was 19 in W.E.B. Du Bois' Crisis magazine. Du Bois gave voice to the life of Negroes in the U.S. in that time (1921) and offered a political critique of how it needed to change. Hughes created poetry that showcased the beauty of African-Americans and the pain of their American experience, expressing emotions, thoughts and dreams that are common to all human beings. I reread the poems we heard recited: Dreams, Hold Fast to Dreams, I Dream a World, I Play it Cool, Acceptance and Evil. In these brief poems Hughes uses deceptively simple words to express feelings that are deep and insights that are often profound.